Low back pain (LBP) or lumbago is a common disorder involving the muscles, nerves, and bones of the back.

Most people will suffer from a period of low back pain in their lifetimes, and some find that it recurs more frequently.

Pain can vary from a dull constant ache to a sudden sharp feeling.

Approximately 9% to 12% of people (632 million) have LBP at any given point in time, and nearly 25% report having it at some point over any one-month period. About 40% of people have LBP at some point in their lives, with estimates as high as 80% among people in the developed world.

The difficulty most often begins between 20 and 40 years of age.

Men and women are equally affected. Low back pain is more common among people aged between 40 and 80 years, with the overall number of individuals affected expected to increase as the population ages.

Now let's look at the basic features of low back pain and conclusions we can draw, before diving into the details of low back pain signs, symptoms and causes.

Leading on to how the bone structure of our backs works, the pain, low back pain prevention, management, medications, possible surgery, and the role of alternative medicine:

1. Introduction

Back pain ranks as one of the top reasons people miss work or go to their doctor, and it's a leading cause of job loss worldwide. Luckily, you too can take steps to either prevent or alleviate most back pain occurrences. In fact, there are several key steps you can take right now to relieve pain and avoid future back problems. For example, did you know that poor posture can be one of the main causes of back pain? Proper sitting and standing posture can alleviate pain in your back.

It's time to admit that poor posture isn't necessarily the root of back discomfort, although it does play a part. This is because bad posture can stretch out the muscles and ligaments in the back. Headaches, neck pain, and stiff muscles in the neck and shoulders are all indications of this.

Another reason why poor posture is so damaging to your back is that it makes it difficult for you to get relief from serious back pain. This is because it limits your range of motion, which in turn makes it more difficult for you to move your body in ways that relieve your pain. In addition, it puts you at risk for more severe problems down the road, such as muscle atrophy. Even if you do seek medical attention for these symptoms, most doctors will give you a prescription for pain killers to help ease your discomfort.

If you're in the advanced stages of back pain, there are some things you can do for pain relief before seeking treatment from your doctor. For example, there are many natural methods you can use on your own to relieve back pain. These methods include exercising, stretching, using hot and cold therapy, and even nutritional supplements like fish oil. These techniques may not always work as well as treatment from a doctor, but if your back pain is severe or chronic, they could be very helpful to your situation.

When your doctor mentions back pain including straining the ligaments, it usually means that you have injured a ligament or a tendon. The type of injury can determine what course of action your doctor will take next. For example, if you injured a muscle in your back, your doctor may suggest rest until the muscle is fully healed. On the other hand, if you have torn a muscle in your shoulder, your doctor may recommend surgery. These treatments can be very dangerous if done by a doctor without enough experience, since they may cause more damage than the initial injury.

Whether or not back pain is a simple condition or it has a serious medical problem, it is important to keep your physician informed of any changes in your health. Some conditions, such as spinal stenosis or osteoporosis, can cause symptoms that are similar to low back pain. They can also affect your ability to walk and your posture, which can put you at risk for falls and serious medical problems. Back pain can easily become a serious medical problem, so it's best to know what causes it so that you can treat it appropriately.

1.1 How Medics Classify Back Pain by Its Duration

Low back pain may be classified by duration as:

- acute (pain lasting less than 6 weeks),

- sub-chronic (6 to 12 weeks), or

- chronic (more than 12 weeks).

The condition may be further classified by the underlying cause as either mechanical, non-mechanical, or referred pain.

1.2 How Long Low Back Pain Lasts for Most People

The symptoms of low back pain usually improve within a few weeks from the time they start, with 40-90% of people recovered by six weeks.

In most episodes of low back pain, a specific underlying cause is not identified or even looked for, with the pain believed to be due to mechanical problems such as muscle or joint strain.

1.3 Always be Thoughtful to Consider The Possibility of Serious Underlying Causes

If the pain does not go away with conservative treatment or if it is accompanied by “red flags” such as unexplained weight loss, fever, or significant problems with feeling or movement, further testing may be needed to look for a serious underlying problem.

In most cases, imaging tools such as X-ray computed tomography are not useful and carry their own risks. Despite this, the use of imaging in low back pain has increased.

1.4 Damaged Intervertebral Discs and the Straight Leg Raise Test

Some low back pain is caused by damaged intervertebral discs, and the straight leg raise test is useful to identify this cause. In those with chronic pain, the pain processing system may malfunction, causing large amounts of pain in response to non-serious events.

Initial management with non-medication based treatments is recommended. NSAIDs are recommended if these are not sufficiently effective.

1.5 A Golden Rule of Low Back Pain – Keep Moving if You Can

Normal activity should be continued as much as the pain allows.

Medications are recommended for the duration that they are helpful. A number of other options are available for those who do not improve with the usual treatment.

1.6 Use of Opioids When Simple Pain Medications are Inadequate – Addiction Risk!

Opioids may be useful if simple pain medications are not enough, but they are not generally recommended due to side effects. Surgery may be beneficial for those with disc-related chronic pain and disability or spinal stenosis.

Opioids attach to proteins called opioid receptors on nerve cells in the brain, spinal cord, gut and other parts of the body. When this happens, the opioids block pain messages sent from the body through the spinal cord to the brain.

While they can effectively relieve pain, opioids carry some risks and can be highly addictive. The risk of addiction is especially high when opioids are used to manage chronic pain over a long period of time.

1.7 The Role of Surgery for Back Pain Relief

Surgery may be beneficial for those with disc-related chronic pain and disability or spinal stenosis. No clear benefit has been found for other cases of non-specific low back pain.

Low back pain often affects mood, which may be improved by counselling or antidepressants.

Additionally, there are many alternative medicine therapies, including the Alexander technique and herbal remedies, but there is not enough evidence to recommend them confidently. The evidence for chiropractic care and spinal manipulation is mixed.

2. Low Back Pain in Detail

2.1 Signs and Symptoms

In the common presentation of acute low back pain, pain develops after movements that involve lifting, twisting, or forward-bending.

The symptoms may start soon after the movements or upon waking up the following morning. The description of the symptoms may range from tenderness at a particular point to diffuse pain.

It may or may not worsen with certain movements, such as raising a leg, or positions, such as sitting or standing. Pain radiating down the legs (known as sciatica) may be present.

The first experience of acute low back pain is typically between the ages of 20 and 40. This is often a person's first reason to see a medical professional as an adult.

Recurrent episodes occur in more than half of people with the repeated episodes being generally more painful than the first.

Other problems may occur along with low back pain.

Chronic low back pain is associated with sleep problems, including a greater amount of time needed to fall asleep, disturbances during sleep, a shorter duration of sleep, and less satisfaction with sleep.

In addition, a majority of those with chronic low back pain show symptoms of depression or anxiety.

2.2 Causes

Low back pain is not a specific disease but rather a complaint that may be caused by a large number of underlying problems of varying levels of seriousness.

The majority of LBP does not have a clear cause but is believed to be the result of non-serious muscle or skeletal issues such as sprains or strains.

Wide-Ranging Back Pain Causes

Obesity, smoking, weight gain during pregnancy, stress, poor physical condition, poor posture and adopting a poor sleeping position may also contribute to low back pain.

A full list of possible causes includes many less common conditions.

Physical Causes

Physical causes may include:

- osteoarthritis,

- degeneration of the discs between the vertebrae or a spinal disc herniation, broken vertebra(e) (such as from osteoporosis) or,

- rarely, an infection or tumour of the spine.

Additional Causes of Back Pain for Women

Women may have acute low back pain from medical conditions affecting the female reproductive system, including endometriosis, ovarian cysts, ovarian cancer, or uterine fibroids.

Nearly half of all pregnant women report pain in the lower back or sacral area during pregnancy, due to changes in their posture and centre of gravity causing muscle and ligament strain.

2.3 The 4 Main Categories of Back Pain

Low back pain can be broadly classified into four main categories:

- Musculoskeletal – mechanical (including muscle strain, muscle spasm, or osteoarthritis); herniated nucleus pulposus, herniated disk; spinal stenosis; or compression fracture

- Inflammatory – HLA-B27 associated arthritis including ankylosing spondylitis, reactive arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and inflammatory bowel disease

- Malignancy – bone metastasis from lung, breast, prostate, thyroid, among others

- Infectious – osteomyelitis; abscess

Low back pain can also be caused by a urinary tract infection.

3. Structures of the Human Back

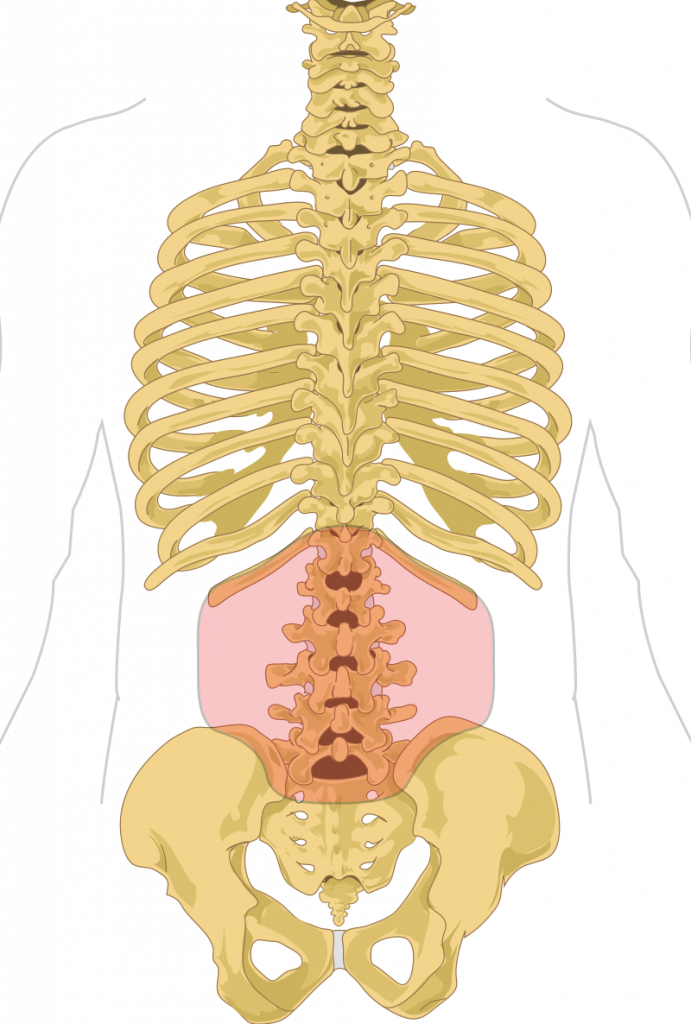

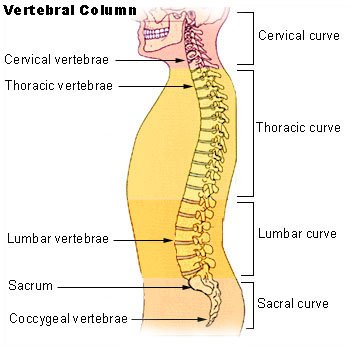

3.1 Vertebrae

The lumbar (or lower back) region is made up of five vertebrae (L1-L5), sometimes including the sacrum.

3.2 Discs

In between these vertebrae are fibrocartilaginous discs, which act as cushions, preventing the vertebrae from rubbing together while at the same time protecting the spinal cord.

3.3 Nerves

Nerves come from and go to the spinal cord through specific openings between the vertebrae, providing the skin with sensations and messages to muscles.

3.4 Ligaments and Muscles

The stability of the spine is provided by the ligaments and muscles of the back and abdomen. Small joints called facet joints limit and direct the motion of the spine.

The multifidus muscles run up and down along the back of the spine and are important for keeping the spine straight and stable during many common movements such as sitting, walking and lifting.

A problem with these muscles is often found in someone with chronic low back pain because the back pain causes the person to use the back muscles improperly in trying to avoid the pain.

The problem with the multifidus muscles continues even after the pain goes away, and is probably an important reason why the pain comes back.

3.5 Teaching the Use of Muscles During Pain

Teaching people with chronic low back pain how to use these muscles is recommended as part of a recovery program.

An intervertebral disc has a gelatinous core surrounded by a fibrous ring. When in its normal, uninjured state, most of the disc is not served by either the circulatory or nervous systems – blood and nerves only run to the outside of the disc.

3.6 How Aging Affects the Spine

Specialized cells that can survive without direct blood supply are in the inside of the disc. Over time, the discs lose flexibility and the ability to absorb physical forces.

This decreased ability to handle physical forces increases stresses on other parts of the spine, causing the ligaments of the spine to thicken and bony growths to develop on the vertebrae.

As a result, there is less space through which the spinal cord and nerve roots may pass.

3.7 Disc Degeneration

When a disc degenerates as a result of injury or disease, the makeup of a disc may change.

When this occurs blood vessels and nerves may grow into its interior and/or herniated disc material can push directly on a nerve root.

Any of these changes may result in back pain.

4. How We Sense Pain

Pain is generally an unpleasant feeling in response to an event that either damages or can potentially damage the body's tissues.

4.1 Steps in the Process of Feeling Pain

There are four main steps in the process of feeling pain: transduction, transmission, perception, and modulation.

The nerve cells that detect pain have cell bodies located in the dorsal root ganglia and fibres that transmit these signals to the spinal cord.

The process of pain sensation starts when the pain-causing event triggers the endings of appropriate sensory nerve cells. This type of cell converts the event into an electrical signal by transduction.

Several different types of nerve fibres carry out the transmission of the electrical signal from the transducing cell to the posterior horn of the spinal cord, from there to the brain stem, and then from the brain stem to the various parts of the brain such as the thalamus and the limbic system. In the brain, the pain signals are processed and given context in the process of pain perception. Through modulation, the brain can modify the sending of further nerve impulses by decreasing or increasing the release of neurotransmitters.

Parts of the pain sensation and processing system may not function properly; creating the feeling of pain when no outside cause exists, signalling too much pain from a particular cause, or signalling pain from a normally non-painful event. Additionally, the pain modulation mechanisms may not function properly. These phenomena are involved in chronic pain.

5. Diagnosis

As the structure of the back is complex and the reporting of pain is subjective and affected by social factors, the diagnosis of low back pain is not straightforward.

While most low back pain is caused by muscle and joint problems, this cause must be separated from neurological problems, spinal tumours, fracture of the spine, and infections, among others.

5.1 More Details on Back Pain Classification

There are a number of ways to classify low back pain with no consensus that any one method is best.

There are three general types of low back pain by cause:

- mechanical back pain (including nonspecific musculoskeletal strains, herniated discs, compressed nerve roots, degenerative discs or joint disease, and broken vertebra),

- non-mechanical back pain (tumours, inflammatory conditions such as spondyloarthritis, and infections), and

- referred pain from internal organs (gallbladder disease, kidney stones, kidney infections, and aortic aneurysm, among others).

5.2 Mechanical or Musculoskeletal Problems

Mechanical or musculoskeletal problems underlie most cases (around 90% or more), and of those, most (around 75%) do not have a specific cause identified but are thought to be due to muscle strain or injury to ligaments. Rarely, complaints of low back pain result from systemic or psychological problems, such as fibromyalgia and somatoform disorders.

Low back pain may be classified based on the signs and symptoms.

5.3 Diffuse and Nonspecific Pain

Diffuse pain that does not change in response to particular movements, and is localized to the lower back without radiating beyond the buttocks, is classified as nonspecific, the most common classification.

Pain that radiates down the leg below the knee, is located on one side (in the case of disc herniation) or is on both sides (in spinal stenosis), and changes in severity in response to certain positions or manoeuvres is radicular, making up 7% of cases.

5.4 Pain Associated with Red Flags – Trauma Fever History of Cancer or Significant Muscle Weakness

Pain that is accompanied by red flags such as trauma, fever, a history of cancer or significant muscle weakness may indicate a more serious underlying problem and is classified as needing urgent or specialized attention.

The symptoms can also be classified by duration as acute, sub-chronic (also known as sub-acute), or chronic.

The specific duration required to meet each of these is not universally agreed upon, but generally, pain lasting less than six weeks is classified as acute, pain lasting six to twelve weeks is sub-chronic, and more than twelve weeks is chronic.

Management and prognosis may change based on the duration of symptoms.

5.5 Indications Which Point to the Need for Further Testing

The presence of certain signs, termed red flags, indicate the need for further testing to look for more serious underlying problems, which may require immediate or specific treatment.

The presence of a red flag does not mean that there is a significant problem. It is only suggestive, and most people with red flags have no serious underlying problem.

If no red flags are present, performing diagnostic imaging or laboratory testing in the first four weeks after the start of the symptoms has not been shown to be useful.

The usefulness of many red flags is poorly supported by evidence.

The most useful for detecting a fracture are:

- older age,

- corticosteroid use, and

- significant trauma especially if it results in skin markings.

The best determinant of the presence of cancer is a history of the same.

With other causes ruled out, people with non-specific low back pain are typically treated symptomatically, without exact determination of the cause.

Efforts to uncover factors that might complicate the diagnosis, such as depression, substance abuse, or an agenda concerning insurance payments may be helpful.

5.6 Diagnostic Tests

Imaging is indicated when there are red flags, ongoing neurological symptoms that do not resolve, or ongoing or worsening pain.

In particular, early use of imaging (either MRI or CT) is recommended for suspected cancer, infection, or cauda equina syndrome. MRI is slightly better than CT for identifying disc disease; the two technologies are equally useful for diagnosing spinal stenosis.

Only a few physical diagnostic tests are helpful.

The straight leg raise test is almost always positive in those with disc herniation. Lumbar provocative discography may be useful to identify a specific disc causing pain in those with chronic high levels of low back pain.

Similarly, therapeutic procedures such as nerve blocks can be used to determine a specific source of pain.

5.7 Recognizing the Limits to Productive Testing

Some evidence supports the use of facet joint injections, transforminal epidural injections and sacroiliac injections as diagnostic tests.

Most other physical tests, such as evaluating for scoliosis, muscle weakness or wasting, and impaired reflexes, are of little use.

Complaints of low back pain are one of the most common reasons people visit doctors. For pain that has lasted only a few weeks, the pain is likely to subside on its own.

Thus, if a person's medical history and physical examination do not suggest a specific disease as the cause, medical societies advise against imaging tests such as X-rays, CT scans, and MRIs. Individuals may want such tests but, unless red flags are present, they are unnecessary health care.

Routine imaging increases costs is associated with higher rates of surgery with no overall benefit, and the radiation used may be harmful to one's health.

Fewer than 1% of imaging tests identify the cause of the problem. Imaging may also detect harmless abnormalities, encouraging people to request further unnecessary testing or to worry.

Even so, MRI scans of the lumbar region increased by more than 300% among United States Medicare beneficiaries from 1994 to 2006.

6.0 Pain Prevention

Exercise appears to be useful for preventing low back pain.

6.1 Exercise

Exercise is also probably effective in preventing recurrences in those with pain that has lasted more than six weeks.

6.2 Mattress Choice

Medium-firm mattresses are more beneficial for chronic pain than firm mattresses.

There is no quality data that supports medium-firm mattresses over firm mattresses.

A few studies that have contradicted this notion have also failed to include sleep posture and mattress firmness.

The most comfortable sleep surface may be preferred.

6.3 Use of Back Belts

There is little to no evidence that back belts are any more helpful in preventing low back pain than education about proper lifting techniques.

6.4 Shoe Insoles

Shoe insoles do not help prevent low back pain.

7. Pain Management

Most people with acute or subacute low back pain improve over time no matter the treatment. There is often improvement within the first month.

7.1 Recommendations

Recommendations include remaining active, avoiding activity that worsens the pain, and understanding self-care of the symptoms.

Management of low back pain depends on which of the three general categories is the cause: mechanical problems, non-mechanical problems, or referred pain.

Goals are to Restore Normal Function

For acute pain that is causing only mild to moderate problems, the goals are to restore normal function, return the individual to work and minimize pain.

Condition is Normally Not Serious

The condition is normally not serious, resolves without much being done, and recovery is helped by attempting to return to normal activities as soon as possible within the limits of pain.

Developing Coping Skills Through Reassurance

Providing individuals with coping skills through reassurance of these facts is useful in speeding recovery. For those with sub-chronic or chronic low back pain, multidisciplinary treatment programs may help. Initial management with non-medication based treatments is recommended, with NSAIDs used if these are not sufficiently effective.

7.2 Non-medication Based Treatments

Non-medication based treatments include:

- superficial heat,

- massage,

- acupuncture, or spinal manipulation.

Acetaminophen and systemic steroids are not recommended as both medications are not effective at improving pain outcomes in acute or subacute low back pain.

7.3 Physical Management and Treatment

Increasing general physical activity has been recommended, but no clear relationship to pain or disability has been found when used for the treatment of an acute episode of pain. For acute pain, low- to moderate-quality evidence supports walking.

7.4 McKenzie Method

Treatment according to McKenzie method is somewhat effective for recurrent acute low back pain, but its benefit in the short term does not appear significant.

7.5 Heat Therapy

There is tentative evidence to support the use of heat therapy for acute and sub-chronic low back pain but little evidence for the use of either heat or cold therapy in chronic pain.

Weak evidence suggests that back belts might decrease the number of missed workdays, but there is nothing to suggest that they will help with the pain.

7.6 Ultrasound and Shock Wave Therapies

Ultrasound and shock wave therapies do not appear effective and therefore are not recommended.

7.7 Lumbar Traction

Lumbar traction lacks effectiveness as an intervention for radicular low back pain. It is also unclear whether lumbar supports are an effective treatment intervention.

7.8 Aerobic Exercises

Aerobic exercises like progressive walking appear useful for subacute and acute low back pain, is strongly recommended for chronic low back pain, and is recommended after surgery.

In terms of directional exercise which try to limit low back pain is recommended in sub-acute, chronic and radicular low back pain.

These exercises only work if they are limiting low back pain.

Exercise programs that incorporate stretching only are not recommended for low back pain.

7.9 Generic or Non-specific Stretching

Generic or non-specific stretching has also been found to not help with acute low back pain.

Stretching, especially with a limited range of motion, can impede the future progression of treatment like limiting strength and limiting exercises.

7.10 Exercise Therapy

Exercise therapy is effective in decreasing pain and improving physical function, trunk muscle strength and mental health for those with chronic low back pain.

It also appears to reduce recurrence rates for as long as six months after the completion of the program and improves long-term function.

There is no evidence that one particular type of exercise therapy is more effective than another.

7.11 The Alexander Technique

The Alexander technique appears useful for chronic back pain, and there is tentative evidence to support the use of yoga.

If a person is motivated with chronic low back pain, it is recommended to use yoga and tai chi as a form of treatment, but not recommended to treat acute or subacute low back pain.

7.12 TENS

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) has not been found to be effective in chronic low back pain.

7.13 Shoe Insoles

Evidence for the use of shoe insoles as a treatment is inconclusive.

7.14 Motor Control Exercise

Motor control exercise involves guided movement and use of normal muscles during simple tasks which then builds to more complex tasks improves pain and function up to 20 weeks but was little different from manual therapy and other forms of exercise.

7.15 Motor Control Exercise with Manual Therapy

Motor control exercise accompanied by manual therapy also produces similar reductions in pain intensity when compared to general strength and condition exercise training, yet only the latter also improved muscle endurance and strength, whilst concurrently decreased self-reported disability.

7.16 Peripheral Nerve Stimulation

Peripheral nerve stimulation, a minimally-invasive procedure, may be useful in cases of chronic low back pain that do not respond to other measures, although the evidence supporting it is not conclusive, and it is not effective for pain that radiates into the leg.

7.17 Aquatic Therapy

Aquatic therapy is recommended as an option in those with other preexisting conditions like extreme obesity, degenerative joint disease, or other conditions that limit progressive walking.

Aquatic therapy is recommended for chronic and subacute low back pain in those with a preexisting condition.

Aquatic therapy is not recommended for people that have no preexisting condition that limits their progressive walking.

7.18 Lumbar Extension Machines

There has been little research that supports the use of lumbar extension machines and thus they are not recommended.

7.19 Pilates for Low Back Pain

There is no quality evidence that supports pilates in low back pain.

8. Medications

The management of low back pain often includes medications for the duration that they are beneficial.

With the first episode when a person experiences low back pain, the hope is a complete cure will be achieved. However, if the problem becomes chronic, the goals may change to pain management and the recovery of as much function as possible. As pain medications are only somewhat effective, expectations regarding their benefit may differ from reality, and this can lead to decreased satisfaction.

The medication typically recommended first are acetaminophen (paracetamol), NSAIDs (though not aspirin), or skeletal muscle relaxants and these are enough for most people.

8.1 Benefits with NSAIDs

The benefits of NSAIDs, however, is often small. High-quality reviews have found acetaminophen (paracetamol) to be no more effective than placebo at improving pain, quality of life, or function.

NSAIDs are more effective for acute episodes than acetaminophen; however, they carry a greater risk of side effects, including kidney failure, stomach ulcers and possibly heart problems.

Thus, NSAIDs are a second choice to acetaminophen, recommended only when the pain is not handled by the latter.

NSAIDs are available in several different classes; there is no evidence to support the use of COX-2 inhibitors over any other class of NSAIDs with respect to benefits. With respect to safety, naproxen may be best. Muscle relaxants may be beneficial.

8.2 Short Term Use of Opioids

If the pain is still not managed adequately, short term use of opioids such as morphine may be useful.

These medications carry a risk of addiction, may have negative interactions with other drugs, and have a greater risk of side effects, including dizziness, nausea, and constipation. The effect of long term use of opioids for lower back pain is unknown.

Opioid treatment for chronic low back pain increases the risk for lifetime illicit drug use. Specialist groups advise against general long-term use of opioids for chronic low back pain.

As of 2016, the CDC has released a guideline for prescribed opioid use in the management of chronic pain.

It states that opioid use is not the preferred treatment when managing chronic pain due to the excessive risks involved.

If prescribed, a person and their clinician should have a realistic plan to discontinue its use in the event that the risks outweigh the benefit.

For older people with chronic pain, opioids may be used in those for whom NSAIDs present too great a risk, including those with diabetes, stomach or heart problems. They may also be useful for a select group of people with neuropathic pain.

8.3 Antidepressants

Antidepressants may be effective for treating chronic pain associated with symptoms of depression, but they have a risk of side effects.

8.4 Antiseizure Drugs

Although the antiseizure drugs gabapentin, pregabalin, and topiramate are sometimes used for chronic low back pain evidence does not support a benefit.

8.5 Systemic Oral Steroids

Systemic oral steroids have not been shown to be useful in low back pain. Facet joint injections and steroid injections into the discs have not been found to be effective in those with persistent, non-radiating pain; however, they may be considered for those with persistent sciatic pain.

8.6 Epidural Corticosteroid Injections

Epidural corticosteroid injections provide a slight and questionable short-term improvement in those with sciatica but are of no long term benefit. There are also concerns of potential side effects.

9. Surgery

Surgery may be useful in those with a herniated disc that is causing significant pain radiating into the leg, significant leg weakness, bladder problems, or loss of bowel control. It may also be useful in those with spinal stenosis. In the absence of these issues, there is no clear evidence of a benefit from surgery.

9.1 Discectomy

Discectomy (the partial removal of a disc that is causing leg pain) can provide pain relief sooner than nonsurgical treatments. Discectomy has better outcomes at one year but not at four to ten years. The less invasive microdiscectomy has not been shown to result in a different outcome than regular discectomy. For most other conditions, there is not enough evidence to provide recommendations for surgical options. The long-term effect surgery has on degenerative disc disease is not clear. Less invasive surgical options have improved recovery times, but evidence regarding effectiveness is insufficient.

9.2 Spinal Fusion

For those with pain localized to the lower back due to disc degeneration, fair evidence supports spinal fusion as equal to intensive physical therapy and slightly better than low-intensity nonsurgical measures.

Fusion may be considered for those with low back pain from acquired displaced vertebra that does not improve with conservative treatment, although only a few of those who have spinal fusion experience good results.

There are a number of different surgical procedures to achieve fusion, with no clear evidence of one being better than the others. Adding spinal implant devices during fusion increases the risks but provides no added improvement in pain or function.

10. Application of Alternative Medicine for Low Back Pain

It is unclear if among those with non-chronic back pain alternative treatments are useful. Chiropractic care or spinal manipulation therapy (SMT) appears similar to other recommended treatments.

National guidelines reach different conclusions, with some not recommending spinal manipulation, some describing manipulation as optional, and others recommending a short course for those who do not improve with other treatments.

10.1 Spinal Manipulation

A 2017 review recommended spinal manipulation based on low-quality evidence.

Manipulation under anaesthesia, or medically assisted manipulation, has not enough evidence to make any confident recommendation.

Spinal manipulation does not have significant benefits over motor control exercises.

10.2 Acupuncture

Acupuncture is no better than placebo, usual care, or sham acupuncture for nonspecific acute pain or sub-chronic pain.

For those with chronic pain, it improves pain a little more than no treatment and about the same as medications, but it does not help with disability.

This pain benefit is only present right after treatment and not at follow-up.

Acupuncture may be a reasonable method to try for those with chronic pain that does not respond to other treatments like conservative care and medications.

10.3 Massage Therapy

Massage therapy does not appear to provide many benefits for acute low back pain.

A 2015 Cochrane review found that for acute low back pain massage therapy was better than no treatment for pain only in the short-term. There was no effect for improving function.

For chronic low back pain, massage therapy was no better than no treatment for both pain and function, though only in the short-term.

The overall quality of the evidence was low and the authors conclude that massage therapy is generally not an effective treatment for low back pain.

Massage therapy is recommended for selected people with subacute and chronic low back pain, but it should be paired with another form of treatment like aerobic or strength exercises.

For acute or chronic radicular pain syndromes, massage therapy is recommended only if low back pain is considered a symptom.

Mechanical massage tools are not recommended for the treatment of any form of low back pain.

10.4 Prolotherapy

Prolotherapy – the practice of injecting solutions into joints (or other areas) to cause inflammation and thereby stimulate the body's healing response – has not been found to be effective by itself, although it may be helpful when added to another therapy.

10.5 Herbal Medicines

Herbal medicines, as a whole, are poorly supported by evidence.

The herbal treatments Devil's claw and white willow may reduce the number of individuals reporting high levels of pain; however, for those taking pain relievers, this difference is not significant.

Capsicum, in the form of either a gel or a plaster cast, has been found to reduce pain and increase function.

10.6 Behavioural Therapy

Behavioural therapy may be useful for chronic pain.

There are several types available, including:

- operant conditioning, which uses reinforcement to reduce undesirable behaviours and increase desirable behaviours;

- cognitive behavioural therapy, which helps people identify and correct negative thinking and behaviour; and

- respondent conditioning, which can modify an individual's physiological response to pain.

The benefit however is small. Medical providers may develop an integrated program of behavioural therapies.

10.7 Mindfulness-based Stress Reduction

The evidence is inconclusive as to whether mindfulness-based stress reduction reduces chronic back pain intensity or associated disability, although it suggests that it may be useful in improving the acceptance of existing pain.

10.8 NRT MBR and KT Tape

Tentative evidence supports neuroreflexotherapy (NRT), in which small pieces of metal are placed just under the skin of the ear and back, for non-specific low back pain.

Multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation (MBR), targeting physical and psychological aspects, may improve back pain but the evidence is limited. There is a lack of good quality evidence to support the use of radiofrequency denervation for pain relief.

KT Tape has been found to be no different for the management of chronic non-specific low back pain than other established pain management strategies.

10.9 Education

There is strong evidence that education may improve low back pain, with a 2.5 hour educational session more effective than usual care for helping people return to work in the short- and long-term.

This was more effective for people with acute rather than chronic back pain.

11. Conclusion

11.1 Acute Low Back Pain

Overall, the outcome for acute low back pain is positive. Pain and disability usually improve a great deal in the first six weeks, with complete recovery reported by 40 to 90%.

In those who still have symptoms after six weeks, improvement is generally slower with only small gains up to one year.

At one year, pain and disability levels are low to minimal in most people. Distress, previous low back pain, and job satisfaction are predictors of long-term outcome after an episode of acute pain.

Certain psychological problems such as depression, or unhappiness due to loss of employment may prolong the episode of low back pain. Following the first episode of back pain, recurrences occur in more than half of people.

11.2 Persistent Low Back Pain

For persistent low back pain, the short-term outcome is also positive, with improvement in the first six weeks but very little improvement after that.

At one year, those with chronic low back pain usually continue to have moderate pain and disability.

11.3 Risk of Long-term Disability

People at higher risk of long-term disability include those with poor coping skills or with fear of activity (2.5 times more likely to have poor outcomes at one year), those with a poor ability to cope with pain, functional impairments, poor general health, or a significant psychiatric or psychological component to the pain (Waddell's signs).

11.4 Influence of Expectations

Prognosis may be influenced by expectations, with those having positive expectations of recovery related to a higher likelihood of returning to work and overall outcomes.

This Guide was based upon the information at www.en.wikipedia.org in May 2021, by simple editing.

Disclaimer

The information provided is not advice, and should not be treated as such. It is provided without any representations or warranties, express or implied. It is provided on the basis that it makes no representations or warranties in relation to the information. The publisher does not warrant that the information is complete, true, accurate, up-to-date, or non-misleading. You must not rely on the information as an alternative to medical advice from your doctor or other professional healthcare providers. If you have any specific questions about any medical matter you should consult your doctor or another professional healthcare provider. If you think you may be suffering from any medical condition you should seek immediate medical attention. You should never delay seeking medical advice, disregard medical advice, or discontinue medical treatment because of information in this publication.

This document is provided for personal use only and is not for distribution or sale.